During the Greek “Golden Age” playwrights, artists, historians and philosophers flocked to Athens from all over the Mediterranean to debate ideas and discuss the fundamental questions of life: What is “justice”? What is the “good life”? What is an “ideal city-state”?

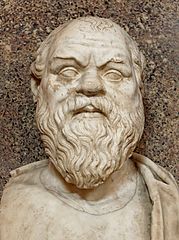

One of the greatest of these philosophers was the Athenian, Socrates (c. 469 – 399 BC), whose style of philosophical questioning gained him a large following of admirers. He spent his life interrogating the opinions and beliefs of people in the public squares of Athens. He is best known for inventing “the Socratic method” – a form of critical questioning which he used to expose people’s underlying beliefs and the limits of their knowledge.

Socrates did not produce any written material during his lifetime, so his philosophical thought is only known through the writing of others, most notably through Plato’s Dialogues (see Plato below). In these, Plato portrays Socrates as a man with an immensely powerful mind and razor-sharp wit, which he often uses to cut his interlocutors down to size.

Unfortunately, it seems that Socrates’ constant questioning of his fellow citizens may have made him some powerful enemies. In 399 BC, he was sentenced to death after being found guilty of charges of impiety (he was accused of not worshipping the Gods of the city) and “corrupting the youth” of Athens.

As a general introduction to Socrates we recommend starting with the Penguin edition of the Early Socratic Dialogues (above right) which includes the dialogues Ion, a debate on poetic inspiration; Laches, in which Socrates seeks to define bravery; and Euthydemus, which considers the relationship between philosophy and politics. This edition also includes an introduction to each dialogue and explanatory notes that provide an excellent guide for a new reader of these works.

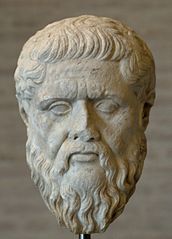

Plato (c. 427— c.347 BC) was a student of Socrates and a hugely influential philosopher in his own right. He set up an Academy to teach Socrates’ ideas to the young men of Athens and he also wrote the Dialogues. These are discussions of moral and philosophical problems between two or more people in which Socrates appears as the principal character alongside other philosophers of the time (including many of the Sophists).

To Plato, there was a world of difference between the philosophical approach of Socrates and the teachings of the Sophists. While the Sophists used rhetorical flourishes to appeal to people’s emotions in order to win a debate, Socrates aimed to use his skills of reasoning to try to discover the truth of the matter. For Socrates, the point was not to win the debate but to gain a better understanding of the world.

By far the most famous of Plato’s dialogues is The Republic which depicts a discussion between Socrates and a number of interlocutors on the topic of justice and the order and character of an ideal form of city-state. While Plato does not play any role in the dialogue, most scholars believe that Plato is simply using the voice of Socrates as a vehicle for his own views. Whatever the case may be, The Republic is an impressive work of philosophy, bringing together ideas on ethics, politics, morality, epistemology and ontology into one overarching framework. Indeed, it was the inspiration for many great works of political philosophy produced centuries later.

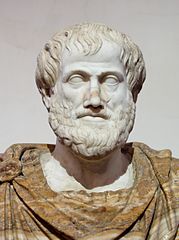

One of Plato’s students at the Academy was the budding philosopher, Aristotle (c.384 BC – 322 BC) who later, became one of Plato’s greatest critics. He studied at the Academy for 20 years, but when Plato died he left Athens and moved to Iona to study wildlife. In 343 BC, he was famously summoned to the court of Philip II of Macedon who asked him to tutor his son, Alexander – the boy who was eventually to become Alexander the Great. Aristotle then returned to Athens in 335 BC where he founded his own school, the Lyceum. While teaching there he produced a large volume of written work, spanning a broad range of subjects including the sciences, politics, philosophy, linguistics and the arts.

Unlike Plato, Aristotle believed that knowledge was acquired through direct observation rather than through reasoning alone. In his work, Politics, he examined the different political regimes existing across Greece at the time and discussed their relative strengths and weaknesses. For Aristotle, the best form of government was one that provided individuals with the opportunity to pursue a “good life”. In another of his important works, Nicomachean Ethics, he set out his ideas on what this “good life” entailed, namely the pursuit of a virtuous character.

Aristotle’s practical, empirical approach to the study of politics contrasted directly with his mentor Plato, who had developed his ideal form of city-state in The Republic through abstract reasoning alone. This difference is depicted in the large featured image at the start of this post, taken from a painting called The School of Athens by the Italian artist Raphael. On the left, is Plato, depicted as a wise, old man with his hand raised to the sky. He is talking to his younger student, Aristotle on the right, whose hand is gesturing to the floor. Plato’s hand gesture is widely thought to represent his philosophical theory that Ideas – the true nature of things – exist in a spiritual realm outside of the physical world and are accessed through reasoning alone. Aristotle’s gesture, meanwhile, represents his belief that knowledge comes from direct observation of the physical world, and that ideas must be rooted in empirical evidence.

Together, these three thinkers – Socrates, Plato and Aristotle – are now considered some of the most influential philosophers of all time. Between them, they laid the foundations for Western philosophical thought, and their ideas continue to be studied in classrooms across the world today.