In his book, A History of Economics: the Past as the Present, JK Galbraith takes us on a fascinating journey through the history of economic thought, exploring some of the most important ideas that have shaped our understanding of the world today. Starting in Ancient Greece, he introduces us to the competing arguments of Plato and Aristotle on the organisation of the economy and its underpinning motivating force: should it be communism (as Plato argued) or self-interest (as put forward by his pupil Aristotle)? In Ancient Rome, he draws our attention to the development of private property rights; an economic institution that laid the foundation for Western capitalist societies in the centuries to come. During the Middle Ages, he presents us with the ponderings of the medieval philosopher, Thomas Aquinas, who questioned the morality of money making and the taking of interest. And in the 15th to 18th centuries, Galbraith describes how negative attitudes towards the pursuit of wealth were overturned in the era of Merchant Capitalism, when joint stock companies – the precursor to the modern corporation – were first invented to fund voyages to distant lands in the pursuit of exotic goods and silver and gold.

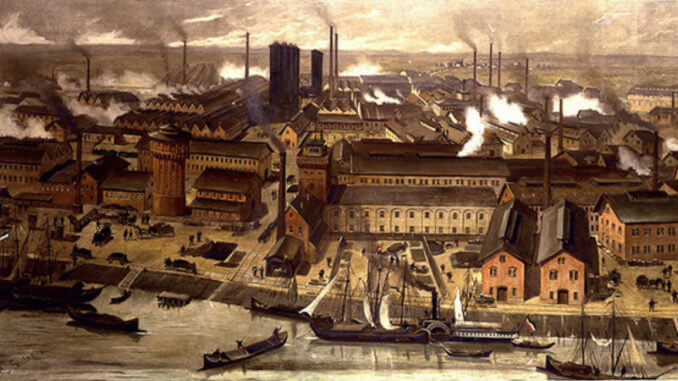

It is with the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and 19th centuries, however, that Galbraith’s narrative really picks up pace; a period where economic power shifted away from the merchant (the purchaser of goods) towards the industrialist (the producer of goods), with capital increasingly being invested in factories, machinery and wages. It was this period of immense social change that brought about arguably two of the greatest economic thinkers of all time: Adam Smith, a staunch advocate of the developing capitalist economy, and Karl Marx, one of its most powerful critics.

Adam Smith and the Classical School of Economic Thought

As Galbraith explains, it was Adam Smith’s ground-breaking work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) that provided the foundations for what later economists – such as Jean-Baptiste Say, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo – would develop into the classical school of economic thought: a framework of guiding principles and theories regarding the inner workings of the economy. This group of economists were firm advocates of free markets and free trade, and emphasised the importance of competition amongst businesses and workers to drive efficiency and economic progress. One of the central assumptions of their economic theory was that the economy was self-regulating, by which they meant it had a tendency to return to a steady state of equilibrium over time. As such, they believed the economy would perform best when the government left it alone; a practice which has since become associated with the French term “laissez-faire”.

As for the driving force behind the economy, Adam Smith famously attributed this to one of the most basic human instincts:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love”. 1

Smith later added that individuals acting in their own self-interest would be led by the “invisible hand” of the market to promote the good of society more effectively than anyone who intended to do so. As Galbraith remarks, this was an extraordinary statement at a time when society still viewed the pursuit of wealth with some suspicion. With a stroke of his pen, Adam Smith had rebranded the self-interested man as a champion of the public good; a claim which had a profound impact on social attitudes at the time, and continues to do so to the present day.

These classical ideas – the importance of competition, free trade and free markets, the need for minimal government intervention in the economy, and the role of self-interest in achieving the greatest public good – would dominate economic thought, at least up until the Great Depression in the early twentieth century. Indeed many of the central tenets of the classical framework are still taught to economics students around the world today. However, while Adam Smith and the classical economists undoubtedly shaped the subject of economics, Galbraith points out that it was Karl Marx’s whole-hearted rejection of the classical orthodoxy and his critique of the capitalist order that shaped the history of the political world by giving birth to the Communist movement.

Karl Marx: A Critique of the Classical System

During the 19th century, Marx fundamentally challenged the classical economists’ assertions that the economy had a tendency to return to a steady state of equilibrium over time. As Galbraith explains, Marx saw economic, social and political life as being in a “process of constant transformation”, the relationship between workers, employers, and the state subject to continuous change over time. Furthermore, Marx argued that the capitalist system was inherently predisposed towards crises of overproduction and unemployment; an issue that was not recognised in classical economic theory, but would gain more widespread acknowledgement during the twentieth century. Finally, and perhaps most famously, Marx was concerned about the distribution of power within the capitalist framework, a topic that was universally ignored by classical economists. In his famous pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto, Marx and his co-author Friedrich Engels argued that capitalism created divisions in society between the rich owners of productive capital and the poor, property-less working classes who – having no alternative form of income – were exploited for their labour. To relieve their suffering at the hands of the capitalists, Marx predicted that the working classes would rise up and take control of the means of production, ushering in a new era of communism.

To relieve their suffering at the hands of the capitalists, Marx predicted that the working classes would rise up and take control of the means of production, ushering in a new era of communism.

Economics in the Twentieth Century: Keynes and The Great Depression

The final stage of Galbraith’s journey brings us to the work of two of the twentieth century’s most influential economists: John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman. The economic theories of the former were born out of the economic and political context of the Great Depression: a period of economic history which began in October 1929 when the US stock market crashed, precipitating the deepest and longest economic downturn of the century. In the US, industrial production dropped by over 40%, unemployment reached 25%, and deflation set in, with the prices of goods and services falling at an annual rate of around 10%. As the years passed and dire economic conditions persisted, policymakers frantically searched for solutions to turn the economy around. However, as Galbraith points out, no economic theory had been developed that could help resolve the crisis; the classical framework that began with the work of Adam Smith did not even recognise the existence of depressions as it assumed the economy would always return to a steady state of equilibrium and full employment over time.

Keynes argued that equilibrium could occur and persist at different, and even severe, levels of unemployment within the economy.

These ideas were heavily criticised by classical economists who could not get on board with the principle of government intervention in the economy, and who felt that the borrowing required to cover government spending was an irresponsible use of public funds. However, as Galbraith notes, other younger economists were more open to Keynes’ ideas, and those that found themselves in positions of political power were able to push for his theories to be put into practice.

Economics in the Twentieth Century: Friedman and the Rise of Monetarism

The second half of the 20th century saw a decline in the popularity of Keynesian ideas. According to Galbraith, this was, in part, due to political problems regarding the implementation of his theories. For while Keynes advocated government expenditure to stimulate the economy in times of recession or depression, his theories also suggested that the opposite action was needed when the economy was booming. That is, at times of low unemployment, when prices were increasing, the government should decrease public spending and increase taxes to prevent inflation from taking hold. Galbraith observes that, in practice, few politicians found this to be a politically agreeable course of action, and as a consequence, it was rare that such economic restraint was shown.

It was in the 1970s, however, that Keynesianism suffered its worst decline. During the prior decade, wage-price inflation had begun to take hold; a problem that was further exacerbated when in 1973 the members of OPEC – the oil-producing states in the Middle East – placed an embargo on oil, causing a significant increase in fuel prices. As prices and wages continued to rise, employers began making cutbacks, ushering in an era of high unemployment and high inflation, or “stagflation” as it came to be known. Keynesian economic theory – which had been developed in the context of the deflationary forces of the Great Depression – was based upon the assumption of an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation, and therefore appeared impotent in the face of high unemployment and high inflation. As Galbraith explains, this provided the context for the economic theories of Milton Friedman – a major critic of Keynes – to come to the fore.

Friedman was a libertarian and, like the classical economists, a powerful opponent of state intervention in the economy. He fundamentally rejected Keynes’ belief that the economy was best controlled via the adjustment of government expenditure and tax rates, and instead promoted his own alternative macro-economic theory known as ‘monetarism’. This emphasised the relationship between the money supply (the total amount of money circulating the economy) and the general level of prices of goods and services. Using statistical models to support his arguments, Friedman held that, after a lag period of a couple of months, price levels would always adjust to reflect movements in the money supply. Price stability could therefore be achieved – and inflation resolved – by controlling the amount of money circulating the economy. The beauty of Friedman’s theory – at least from a classical perspective – was that all this could be accomplished by a central bank rather than by direct government intervention in the economy. By increasing (or decreasing) interest rates, a central bank could inhibit (or encourage) bank lending, which would in turn result in a decrease (or an increase) in the money supply, thereby providing a mechanism to control inflation or deflation.

Friedman promoted an alternative macro-economic theory known as ‘monetarism’, which emphasised the relationship between the money supply and the general level of prices of goods and services in the economy.

Economics Today and Into the Future

Milton Friedman’s theories continue to play a central role in economic policy today. In the US and the UK, central banks still use interest rates as the primary mechanism for controlling inflation. Moreover the policy response to the global recession of 2008 involved the implementation of an expansionary monetary policy, albeit in an unconventional form known as “quantitative easing”. But it is not only the ideas of Friedman that have left their mark; contemporary political and economic debate continually draws its inspiration from the economic ideas of the past. For example, the calls made by politicans (usually on the left of the political spectrum) for ‘fiscal stimulus’ during times of weak economic growth are rooted in the Keynesian economics of the early 20th century; the growing attention being paid to income inequality and the concentration of wealth in society owes its intellectual origins to the 19th century works of Karl Marx (see for example Thomas Piketty’s popular book Capital in the 21st Century); and modern discussions about globalisation, free trade and free markets, rarely take place without touching upon the thoughts of the 18th century economist, Adam Smith and his classical counterparts. As Galbraith asserts, a deep understanding of current economic issues and policies can only be genuinely achieved through an appreciation of the economic ideas and events of the past.

According to Galbraith, the most influential economic ideas have, almost always, emerged as a response to the economic, political and social conditions of their time.

For Galbraith, this sense of optimism about the future of economics should, however, be tempered with a word of warning. For in his view, the discipline has entered into a period of crisis, in part due to its overreliance on the classical economic theories of the past, and in part due to economists’ desire to view their subject as a science. One of the consequences of this has been the development of, and increasing reliance on, mathematical models of the economy which are often based on simplistic assumptions about human nature and unsophisticated representations of complex market dynamics. By doggedly pursuing this scientific approach to economic inquiry, Galbraith believes that economists have succeeded in separating the subject from the complex political and social world in which it is embedded. This has resulted in a complete disregard for important issues such as the exercise of power within the economic system and its effects on workers and consumers. If economics as a subject and its ideas are to remain powerful and relevant in the future, Galbraith argues that they must reflect the social and political world around them. As he puts it:

“Economic ideas are always and intimately a product of their own time and place; they cannot be seen apart from the world they interpret. And the world changes – is, indeed in a constant process of transformation – so economic ideas, if they are to retain relevance must also change.” 2

Further Resources

A History of Economics: The Past as the Present is an excellent and highly accessible book for anyone wishing to learn more about the subject of economics and its history. Whilst we have focused, in this article, on the theories of four major economists – Adam Smith, Marx, Keynes and Friedman – Galbraith’s book covers a wide range of economic thinkers that have had an important impact on the subject today.

JK Galbraith has also published many other notable works in the field of economics including:

- The Great Crash, 1929 which examines the causes, effects and long-term consequences of the Great Depression;

- A Short History of Financial Euphoria which examines some of the major speculative episodes of the last four centuries, from “Tulipomania” in 1636 to “Black Monday” in 1987; and

- The Affluent Society which considers the problem of economic inequality and challenges some deeply held economic myths.

You can also find more video resources on this topic at our Mind Attic YouTube channel playlist.