In 2016 “post-truth” was chosen as the “Word of the Year” by Oxford Dictionaries – a year in which Donald Trump was elected president and the UK voted to leave the EU. During the run up to these major political events, citizens on both sides of the Atlantic were presented with a variety of claims from politicians and online sources designed to appeal to their emotions and sway their vote in a particular direction. Journalists commentating on these events worriedly remarked that we were entering into an era of “post-truth” politics in which “objective facts were becoming less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”1. These concerns were exacerbated by the furore surrounding the US presidential inauguration at the beginning of 2017. While journalists claimed, using photo and video evidence, that there was a smaller crowd in attendance than previous inaugural addresses, advisors to the President asserted that the audience was larger than it had ever been. When challenged over these claims, one of the Presidents’ advisors famously coined the phrase “alternative facts” to explain why her version of events differed to those of the mainstream media.

Given this political backdrop and, in particular, the widespread concerns that we are moving into a “post-truth” world, we thought it was worth spending some time reflecting upon the nature of our knowledge and its relationship to the concept of “truth”. We should warn you: this is not going to be a quick or straightforward post. We will be covering some pretty complex philosophical ideas which question the fundamental pillars of our knowledge. However, if you have never encountered these ideas before, they are well worth spending some time on because they have the potential to dramatically change the way that you think. So let’s start this discussion by considering a basic definition of a term that is often used in the media and within political debate:

Fact (noun) a thing that is known or proved to be true

This definition, provided by the Oxford Dictionaries, immediately raises some interesting philosophical questions: what does it mean to know something? And how can we prove that something is true? Furthermore, how can we even be sure that the truth exists and is singular in nature? Is it possible, for example, for there to be multiple conflicting truths?

These sorts of questions have been debated for centuries and have formed a distinct branch of philosophy known as epistemology – a term which is derived from the Greek words episteme (meaning “knowledge”) and logos (meaning “study of”), and refers to the study of knowledge. Unfortunately, epistemology does not generally feature in the school curriculum or indeed, many University undergraduate courses. This is a great shame because it can play an important role in developing our ability to understand and critique knowledge claims about the world around us. Instead, many students are taught to unthinkingly follow a particular method of inquiry – the scientific method – without ever being aware of its philosophical underpinnings or the ongoing debate around its use within the social sciences.

Acquiring Knowledge in the Social Sciences

While science, or the scientific method, has undoubtedly been incredibly successful in enabling us to predict and explain phenomena within the natural world, its application to problems within the social world – the world of human behaviour and relationships – has been far less effective. Many of the social questions that have exercised philosophers throughout history – on ethics, morality and politics – continue to be fiercely debated today. This lack of progress has stimulated much discussion within academic circles about the best way to pursue knowledge within the social realm. While some thinkers maintain that the scientific method should remain the principle form of investigation, others are highly critical of this approach and have instead advocated the use of alternative methods of inquiry into social affairs – methods which are underpinned by a very different set of philosophical beliefs to the standard fact-based scientific view of the world.

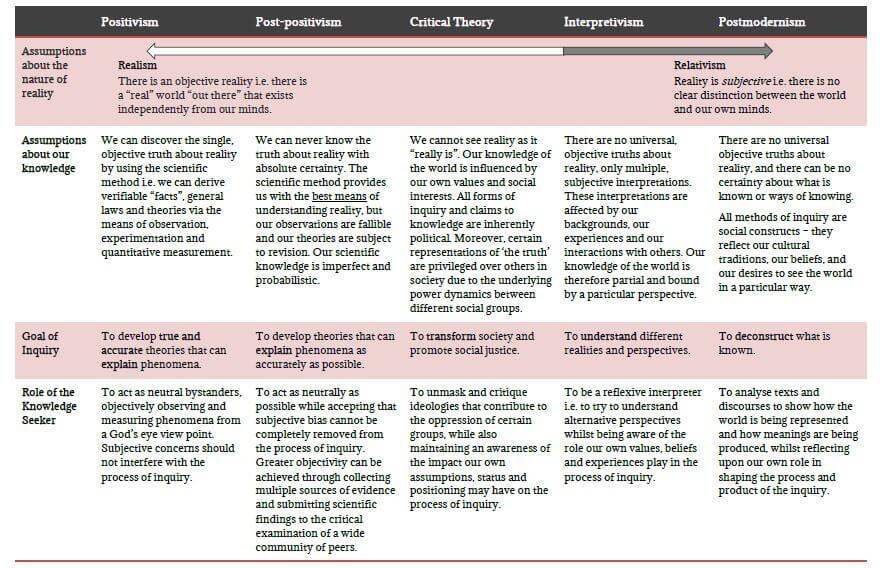

The table below – which you can click on to enlarge – provides a summary of five major contrasting philosophical positions which commonly underpin different types of social research. These include the more familiar scientific perspectives (represented on the left hand side of the table) and the less well known alternative perspectives which challenge the dominant scientific view of world (represented on the right hand side of the table).

It is worth briefly exploring each of these philosophical positions in turn, starting with positivism which advocates a scientific approach to understanding the world.

Positivism

Positivism asserts that the only legitimate form of knowledge about both the natural and social worlds is scientific knowledge, comprised of well substantiated facts, general laws and theories. To understand this viewpoint, it is helpful to explore how positivists think about the nature of reality because this informs their opinions about what counts as knowledge.

Generally speaking, positivists are realists in that they believe in an objective reality. That is to say they think there is a “real” world “out there” that exists independently from us and our minds. To better understand this notion, it is helpful to think for a moment about an everyday object, such as a tree2. According to positivists/realists, trees exist within the world regardless of whether or not we, as humans, are consciously aware of them; that is, they are separate and distinct to us and very much “real”. If the human race was wiped out tomorrow, then trees would continue to exist and their intrinsic features – the characteristics that make them “trees” – would remain.

This belief in an objective reality has very important implications for knowledge, for a positivist would argue that if there are real, distinct objects and phenomena “out there” waiting to be discovered, then there must also be a single objective truth about these phenomena – a true and accurate description that exists separately from us, the knowledge seekers. The goal of all inquiry, therefore, should be to discover this single objective truth.

So how should we go about this task? According to positivists, we can do this by following the scientific method. In short, this involves using our senses to repeatedly observe and measure phenomena, often during carefully controlled experimentation. The aim is to derive “facts” – observable measurements – about the world around us, which are for all intents and purposes considered to be “truths”. These “facts” then provide the building blocks for more complex laws which describe phenomena (usually in the form of a mathematical relationship), and theories which explain how and why we think particular phenomena occur. These laws and theories are then subjected to repeated, systematic testing and refined or rejected by the scientific community on the basis of observational evidence.

Now according to positivist thought, a critically important aspect of the scientific method is the need for “objectivity” on the part of the researcher. That is, we – the knowledge seekers – must act as neutral bystanders, observing and measuring phenomena from a God’s eye view point. Any subjective concerns – such as our values, opinions and beliefs – must not interfere with the process of discovery. By obeying this principle of objectivity and by correctly following the scientific method, positivists have historically argued that we can discover the objective truth about the world around us.

Post-Positivism: An amended version of Positivism

The positivist position has, however, come under sustained criticism over the last century, with some of its most notable critics coming from within the scientific community itself.

One of the first critics was the philosopher Karl Popper who pointed out that scientists can never directly discover the truth about the world around us. This is because they are only able to falsify (disprove) their theories through scientific testing. Popper argued that it was only once all attempts to disprove a theory had failed, that the theory could tentatively be accepted by the scientific community. Even then, there was always the possibility that new evidence could come along that disproved the theory at a future date. Given this, scientists could never accurately claim to be in full possession of the truth about reality; they must always leave the door open to some uncertainty.

Another equally powerful criticism of the positivist framework came from the physicist Thomas Kuhn. He challenged the positivist assumption that scientists were able to objectively observe the world as it “really was”. Instead, Kuhn argued, scientists operate within particular paradigms: they subscribe to a specific theory or a set of beliefs about the world based on their shared values and the communal judgement of the scientific community they are working within. Those beliefs then determine how they should observe and measure phenomena, and indeed what should be observed. Kuhn’s arguments were important because they suggested that science should not be viewed as a completely objective or value-free endeavour, as scientists’ subjective beliefs were playing an important role in the construction of their knowledge.

Popper and Kuhn’s arguments – which have gained widespread acceptance within the scientific community – have ultimately led to a slightly revised version of positivism, known as post-positivism. Like positivists, post-positivists tend to believe in an objective reality – they think that the natural and social worlds consist of “real” things, events and phenomena – and that this reality can be best understood via scientific observation and experimentation. However, unlike positivists, post-positivists concede that we can never know the truth about that reality with absolute certainty because our scientific observations are fallible and our theories are subject to revision. Given this, post-positivists tend to talk in probabilistic, rather than in certain terms about the relationship between their scientific findings and “the truth”.

While post-positivists accept that we cannot achieve objective knowledge about the world in an absolute sense, they still believe that we can strive towards the ideal of objectivity. In particular, they emphasise the need to collect multiple sources of evidence to cross-validate our findings, and they recommend that all knowledge claims are subjected to the critical examination of a wider community of peers. By engaging in these actions, and by endeavouring to act as neutrally as possible during the process of inquiry, post-positivists believe that we can get close to an understanding of reality i.e. we can achieve an approximation of the truth.

Alternative Philosophies: Interpretivism, Critical Theory and Postmodernism

The frameworks of positivism and post-positivism have dominated the natural and social sciences – and indeed society at large – for the last century. However, the belief that science always provides us with the “best” route to knowledge is not shared by all researchers working in the social sciences, some of whom look towards alternative philosophies to guide their research. These include the frameworks of interpretivism, critical theory and postmodernism (see table above) which challenge the assumption that we are able to directly know or approximate the ‘truth’ about reality. To understand these alternative frameworks it is helpful to tackle them in a particular order: we will start with the frameworks of interpretivism and postmodernism before moving on to consider critical theory which shares some aspects in common with all of the frameworks outlined in this post.

Interpretivists and postmodernists both challenge the positivist and post-positivist assumption that there is an independent, objective reality out there waiting to be discovered. Instead, they are more closely aligned with a “relativist” position which asserts that reality is subjective because there is no clear distinction between the world and our own minds. To understand this notion, let’s return for a moment to the example of a tree 3. Whilst a realist would assert that trees are separate and distinct from us and are very much “real”, a relativist would argue that a tree’s existence is inextricably tied to our own; as an object, a tree would be rendered meaningless if humans and human consciousness did not exist. Put another way, a tree is only a “tree” because we have decided it to be so; it is human beings who have given it the label “tree” and have attached particular meanings to it. If the human race was wiped out tomorrow then the word “tree” and its associated meaning would also die with us.

This philosophical belief about the subjective nature of reality, again, has important implications for the development of knowledge because, in contrast to the realist/positivist position, which holds that knowledge is something external and separate to us waiting to be discovered, relativism implies that knowledge comes from within; it is constructed within our own minds. This means that there can be no such thing as universal, objective truths about reality, only multiple, subjective interpretations.

Given this belief that reality exists in the form of mental constructions, it would seem logical to draw the conclusion that there can be as many distinctive, subjective realities as there are people on this planet. However, because we are social animals, our subjective interpretations are often developed through our interactions with others. This means that it is possible for us to form shared understandings and interpretations of the world. Going back to the example of a tree, we can imagine that within some social groups a tree may represent “healing” because it is associated with medicinal treatments, while in another cultural context it may be viewed as a symbol of worship in line with a particular group’s spiritual or religious beliefs. The point is that a tree – or any other object or phenomenon – may carry different meanings for different people and different social groups.

So how can we gain knowledge if reality is subjective? Well interpretivists assert that we should try to understand the different meanings – or the multiple subjective realities – constructed by individuals in their minds. This may be achieved by, for example, conducting in-depth interviews with people about particular topics of interest, or embedding ourselves within different cultural contexts to try and observe phenomena from a different perspective to our own. In contrast to the positivist framework, this approach assumes that we – the knowledge seekers – can never be objective, neutral bystanders, easily separated from the subjects of our inquiry. Rather, we are part and parcel of the social world we are observing and will therefore use our own “interpretive lens” to observe and understand social phenomena. This “lens” consists of our own assumptions, values and beliefs which we have developed through the course of our lives, and is affected by our histories, our lived experiences and our relationships with others. The implication is that our knowledge of the world – as viewed through this “lens” – can only ever be partial, and will always be bound by a particular perspective.

While interpretivists seek to understand the different realities that individuals construct in their minds, postmodernists tend to focus on our processes of inquiry: the choices we make to investigate and represent matters in a particular way. This is because, according to postmodernist thought, all knowledge claims and methods of inquiry are social constructs – they reflect our cultural traditions, our personal beliefs and desires – and as such, they can tell us something important about ourselves and the way we wish to see the world. An important strand of postmodernism is the role of language in knowledge formation. This is because postmodernists do not view language as a vehicle that simply describes or represents reality; rather they see it as a tool that we use to actively construct the world around us. By engaging in the deconstruction of texts and discourses, postmodernists seek to expose the underlying value systems, motivations and assumptions that underpin our claims to knowledge about the world.

While postmodernists deconstruct and critique all forms of knowledge creation, they pay particular attention to “scientific” knowledge developed within the positivist and post-positivist traditions. This is because scientific knowledge generally occupies a privileged position within society, and postmodernists – who are generally distrustful of authority – wish to challenge its power and influence by pointing out the limitations of its methods and claims to objectivity. For example, scientific “facts” and theories – which are often presented in the public domain as the uncontroversial “truth of the matter” – are exposed, by postmodernists, as social constructs: they represent a belief about what is true, on the basis of a set of social practices and rules which we have constructed and labelled as “science”. Moreover, we have not created these scientific rules in a vacuum; postmodernists would argue that they have been developed within a particular cultural and historical context and, as such, they are laden with the values of our time. These values include the notion that human beings are rational and capable of achieving accurate and objective knowledge; an assumption which, for many postmodernists, is questionable. By challenging the foundations of our knowledge in this manner, postmodernists are questioning the notion that we can ever definitively know and understand the world around us.

The final framework we will consider is critical theory, which in line with positivism and post-positivism subscribes to a “realist” position i.e. critical theorists traditionally believe in an objective reality that exists independently from our minds. However, importantly, critical theorists do not agree with the positivist assumption that we can observe this reality as it “really is”. Nor do they agree with post-positivists that we can get close to an objective understanding of reality by acting as neutrally as possible. Instead, critical theorists believe – like interpretivists and postmodernists – that our knowledge of the world is constructed and is, therefore, entirely subjective. Furthermore, they believe that all our subjective interpretations are influenced by our values and social interests. That is, we – as individuals or individuals acting within particular social groups – will construct a version of reality that brings us some type of social advantage. This is not necessarily a conscious choice; we are often unaware of our own biases that lead us to see the world in a particular light.

Of particular interest to critical theorists is the way in which certain subjective interpretations of reality – or particular representations of “the truth” – rise to prominence within society due to the underlying power dynamics between individuals and different social groups. More specifically, they aim to expose instances whereby the beliefs of powerful actors are privileged over the beliefs of other less powerful groups – such as ethnic minorities or women – and are contributing to their oppression. This is because critical theorists are primarily motivated by highlighting and overcoming social injustices in the world. They do this by unmasking the belief systems that are dominant within society and subjecting them to criticism, dismantling and exposing their underpinning assumptions. The feminist movement is a classic example of this. By challenging the prevailing narrative about what women are capable of and what their role in society should be – a narrative which, they would argue, has been historically constructed by a male, ruling elite – feminists have won many concessions, including the right to vote, the right to an education and the right to receive equitable pay. So, in short, rather than purely seeking to understand the social world, critical theorists aim to change it for the better.

Are we moving into a “post-truth” world?

In future posts we will expand on these philosophical positions and their related methods of inquiry, but let us for a moment return to the problem posed at the start of this post. That is, the suggestion we are moving into a “post-truth” world as a result of the declining influence of “objective facts” in political discourse. Now that we have briefly explored a few basic epistemological positions, we are better equipped to analyse this narrative and its underpinning assumptions. In particular, we can see that it is more closely aligned with a positivist perspective in that it assumes that the “best” type of knowledge – upon which “good” political debate depends – is “objective, factual” knowledge because this is what represents “the truth” of the matter. By ignoring “objective facts” and making political decisions on the basis of other, subjective concerns, the implication is that we – as a society – are becoming less rational and to some extent ignorant of “the truth”.

But this “post-truth” narrative is not as simple or uncontroversial as it may first seem. For a start, it could be argued from a post-positivist perspective that “facts” and theories derived from scientific research and quoted in the course of political debate do not represent the absolute truth of the matter; rather, they represent an approximation of the truth because our scientific observations are fallible (we are unable to completely remove subjective bias from our process of inquiry) and our theories are revisable (they can be overturned by the arrival of new, contradictory evidence tomorrow). Given this, it would be more appropriate to claim that we are living in a “pre-truth” rather than a “post-truth” world because, through science, we are continually striving for, but never quite achieving, accurate knowledge of the world around us.

The camp of interpretivists, critical theorists and postmodernists on the other hand would likely argue that the “post-truth” narrative is completely flawed because all claims to knowledge made in the course of political debate are inherently subjective: they represent a particular way of seeing the world that is influenced by our backgrounds, experiences, values, beliefs and our political and social interests. Even “facts” and theories generated via the scientific method are not neutral; they are the result of subjective choices and value-based assumptions made by researchers through the process of inquiry. Given this, political debate could more appropriately be viewed as a contest between competing, subjective realities where there is no “correct” or neutral way to judge between the differing viewpoints being put forward.

This perspective, in which scientific “fact-based” knowledge is considered no more valid than other ways of knowing the world, has been treated with contempt from some corners of the scientific community, with one famous philosopher, Daniel Dennett, even describing it as an “evil” school of thought. Indeed, there is something very unsettling about the notion that there can be no “correct” or neutral way of judging between arguments made in the course of public debate. On the other hand, automatically privileging scientific, “fact-based” knowledge above other ways of knowing the world is not an unproblematic position, particularly if we accept that there are limitations to the scientific method and our abilities to observe phenomena – especially social phenomena – objectively.

Here at the Mind Attic we advocate the adoption of an open-minded approach, whereby we equip ourselves with a variety of frameworks that can enable us to be more critically disposed to the information we receive. That is, we believe we should develop the skills to analyse an argument from a variety of philosophical perspectives. For example, when taking a positivist or post-positivist position we might wish to question: What sources of evidence do they have to back up their claims? Do all these sources point towards the same conclusion? How many other scientists/experts in the field agree with their findings? When acting as interpretivists we might ask: How is this person (or group of people) making sense of the world around them? What, in their background or experience, might be leading them to see the world in this particular way? And how might our own interpretive “lens” be affecting the way that we look at this issue? As critical theorists we might take a slightly more critical orientation and ask: What are this person’s (or group’s) particular economic, political or social interests and how might these be influencing the arguments they are putting forward? Furthermore, how might their arguments benefit certain people within society and disadvantage others? And how might our own status and positioning be affecting the way that we look at this issue? Finally, as postmodernists we might wish to analyse the language being used to construct a particular argument: How is the problem being defined? What value assumptions are being made? How is complexity being opened up or, more importantly, where is it being shut down? In particular, postmodernists would seek to challenge those that provide simple and certain answers to complex questions because, from their perspective, there can be no certainty about what is known or ways of knowing the world. Perhaps Oscar Wilde summed it up best when he said that:

“The pure and simple truth is rarely pure and never simple”

Further Resources

There are many useful books and articles which expand on the ideas presented in this article. These are mainly written with social researchers and PhD students in mind. However, if you are interested in philosophical ideas about the nature of our knowledge and the nature of reality these texts are well worth a read. They include:

- Michael Crotty’s The Foundations of Social Research which we referenced in this article.

- Egon Guba’s The Paradigm Dialog which starts with a useful summary of several epistemological positions.

- Robin Usher and David Scott’s Understanding Educational Research. In particular, we recommend the chapter entitled “A Critique of the Neglected Epistemological Assumptions of Educational Research”.

- Carl Wenning: Scientific Epistemology – How scientists know what they know

For further video resources on this subject please visit our Mind Attic YouTube channel playlist