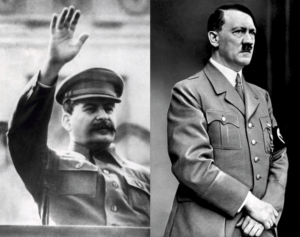

As a Jewish woman born in Hanover, Germany in the early 20th century, the rise of Nazism played a decisive role in Hannah Arendt’s life. In 1933, fearing Nazi persecution, Arendt fled from Germany to the relative safety of France where she worked for an organisation which helped rescue Jewish children from Eastern Europe. While living in France she became interned in a detention camp, but managed to escape and make her way to the US in 1941. It was here that she wrote her fascinating book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, in which she attempted to understand and come to terms with the horrors of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia.

Arendt’s thought-provoking work on totalitarianism stimulated a wide ranging debate on the factors that led to the Nazi and Stalinist regimes, and earned her a reputation as a major thinker in the field of political philosophy. While her theories have been the subject of some criticism and controversy, they have seen something of a revival in recent times given the widespread concerns about the rise of right-wing, populist movements in the US and Europe. The summary below briefly captures some of her thoughts on totalitarian regimes, their chief characteristics, and how they rise to power.

What are the characteristics of “totalitarianism”?

Rather than provide us with an explicit definition of totalitarianism, Arendt chooses to develop our understanding of this political phenomenon through her unfolding account of the Nazi regime in Germany and Stalinist Russia. While it is impossible to do justice to the complexity of Arendt’s narrative here, there are some key points in her text that are worth highlighting.

First, Arendt is keen to stress that, for her at least, the term “totalitarianism” does not simply refer to a system of authoritarian government or single party rule. In her own words:

“Totalitarianism differs essentially from other forms of political oppression known to us such as despotism, tyranny and dictatorship.” 1

So what is it that distinguishes totalitarian regimes from other forms of political dictatorship? According to Arendt, one key distinction is the sheer scale of cruelty and mass murder they inflict upon on the population. Indeed, she even goes so far as to argue that a fully developed system of totalitarian rule is not possible in countries with small populations as they simply “do not control enough human material to allow for total domination and its inherent great losses in population”. 2 In Nazi Germany, for example, she suggests that the totalitarian system was only fully realised once the country conquered new lands during the Second World War. It was this expansion east, she argues, that furnished the Nazis with the large masses of people that made the extermination camps possible.

In addition to the unprecedented scale of human suffering, Arendt suggests a number of other distinguishing features that, together, form the essence of totalitarianism. A crude summary of these is as follows:

- the destruction of the country’s previous social, legal and political traditions;

- the replacement of the political party system – not with a single party dictatorship but – with a mass movement;

- the organisation of the masses along the lines of an ideological doctrine which is unintelligible to outsiders i.e. it has no basis in fact or common sense;

- the demand for total, unrestricted and unconditional loyalty of the individual member to the mass movement;

- a shift in the centre of power from the army to a secret police;

- the use of propaganda and indiscriminate terror to indoctrinate people into the ideology of the movement, leaving individuals unable to argue or think for themselves or even experience their own experiences; and finally

- the establishment of a foreign policy which is explicitly directed towards world domination.

It is perhaps point (6) which underlines one of the most disturbing features of totalitarian regimes: that they find a way of colonising people’s minds, “dominating and terrorising [them] from within”. As Arendt explains, this system of internalised terror – which is more sophisticated than external acts of physical violence – can erode an individual’s ability to think for themselves or make moral judgements about what is right or wrong. In its extreme form, it can create a sense that oneself no longer matters, and that the collective aims of the movement are more important than any individual interests or desires. As Arendt puts it these “fanaticised members” can then no longer be reached by rational argument as “identification with the movement and total conformism seem to have destroyed the very capacity for experience, even if it be as extreme as torture or the fear of death”. 3

So how do totalitarian regimes rise to power?

In her attempt to answer this important question, Arendt exposes what she believes to be a dangerous myth: that leaders of totalitarian movements get into power on the basis of conspiracies or via support from small sections of society. In her view these explanations deny the uncomfortable truth that totalitarian regimes and leaders command and rest upon mass support right up until the end. For example, she maintains that Hitler and Stalin could not have sustained their leadership through the endless crises and intra-party struggles that occurred under their watch without the confidence of large swathes of the population. Nor, she argues, can totalitarian leaders’ popularity simply be attributed to their clever use of propaganda, because invariably they “start their careers by boasting of past crimes and carefully outlining their future ones”. 4

According to Arendt, totalitarian regimes can arise in “socially atomised” societies where there is a mass of politically indifferent people who cannot be held together by any sort of class consciousness or shared economic interest.

In Weimar Germany, Arendt describes how the country’s military defeat in World War One, and the mass unemployment and hyperinflation that followed, provided the catalyst for the weakening of social bonds and the breakdown of the class system. It also resulted in a rapid increase in the number of dissatisfied and desperate people who were full of contempt for their current political rulers who seemed unable to provide any answers to their troubles:

“The fall of protecting class walls transformed the slumbering majorities behind all parties into one great unorganised structureless mass of furious individuals who had nothing in common except their vague apprehension that the hopes of party members were doomed, that, consequently the most responded, articulate and representative members of the community were fools and that all the powers that be were not so much evil as they were equally stupid and fraudulent.” 5

It was this social isolation and political apathy, that Arendt argues, more generally, provides fertile ground for a “strong man” to seize power, who targets and recruits from the politically indifferent masses by offering a fictional story or ideology which claims to explain the source of all societal problems. In Nazi Germany, this strong man was of course Adolf Hitler, and the story he put forward was of a Jewish world conspiracy, whereby the Jews controlled society and wished to take over the world. According to Hitler’s narrative, the Jews were entirely to blame for Germany’s economic decline and were the cause of all the German people’s woes.

As Arendt explains, this fictional story did not need to stand up to the scrutiny of opposing political parties in Germany because the masses had become indifferent to their arguments. Moreover, the people were receptive to this fictional account of the world because it offered them an escape from a reality they could no longer bear – their atomisation, their loss of social status and communal relationships. And although the story had no basis in truth, Arendt argues that the masses were attracted to its simplicity – its ability to completely explain their current circumstances – and its internal consistency, whereby each invented “fact” followed on logically from the previous:

“What convinces masses are not facts, and not even invented facts, but only the consistency of the system of which they are presumably part . . . Totalitarian propaganda thrives on this escape from reality into fiction.” 6

So what can we learn from Arendt’s theories about the rise of totalitarian regimes?

Arendt’s work teaches us many things: that we should be wary of leaders who offer us compelling but simplistic explanations for the problems of our times; that we should always be concerned about political apathy in all its forms and its potential to undermine the legitimacy of our democratic society; that enthusiastic and civic debate – where we think, argue and resolve our differences together – can help strengthen our social bonds and protect us from the loneliness and isolation that makes us vulnerable to tyrannical rule. Most of all, Arendt’s work provides us with an important reminder that we should never be complacent about the potential for the re-emergence of the political forces that led to the rise of totalitarianism and the catastrophic loss of life in the early 20th century.

Notes and Further Resources

The Origins of Totalitarianism is often described as being one of the most important books of the twentieth century. As well as providing an insight into the development of the Nazi and Stalinist totalitarian regimes, it examines the history of Anti-Semitism in Western and Central Europe and analyses the roots and consequences of European imperialist expansion during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. To support and complement your reading of Arendt’s work, we would recommend the following additional resources:

- Margaret Canovan’s two books: The Political Thought of Hannah Arendt and Hannah Arendt: A Reinterpretation of her Political Thought. These books are not readily available on Amazon but should be found in most good public libraries (you can use the links we have provided to perform a search of your local library).

- The BBC Radio 4 programme “In Our Time” recently covered Hannah Arendt’s broader work and this is currently available for download here.

- Alone in Berlin by Hans Fallada is a fictional book which provides an insight into the experience of living under totalitarian rule in Nazi Germany. It captures the absolute fear the regime instilled in people that kept them from engaging in any form or rebellion.

You can also find more video resources at our Mind Attic YouTube channel playlist.