In our article The Nature of Knowledge: Are we Living in a Post-Truth World? we briefly outlined a number of different philosophical approaches to acquiring knowledge about the world around us. These included: positivism and post-positivism, which both assert that the scientific method provides the best means of understanding the natural and social worlds; and interpretivism, critical theory and postmodernism, which challenge the scientific tradition by offering alternative means of exploring and understanding reality. In this article, we will spend some more time discussing the interpretivist position – a particular philosophical approach to inquiry which often underpins research carried out within the fields of sociology and anthropology.

The Interpretive Movement of the 19th century

The interpretive movement developed during the 19th century, when the social sciences were first beginning to emerge as a distinct field of inquiry. At this point in time, the scientific method was fully established as the dominant framework for sourcing knowledge about the natural world – an approach which emphasised rational, objective inquiry based on repeated, systematic observation and measurement. By strictly following the rules of the scientific method, scholars had been able to generate laws and theories which offered explanations for a wide range of natural events – knowledge which gave them the power to control and manipulate our physical environment like never before. Inspired by these incredible discoveries, some social philosophers – most notably August Comte (1798–1857) and Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) – set out to apply the discipline of science to the study of humans and their behaviour. By rigorously observing and measuring aspects of social life in a neutral and objective fashion, these scholars believed they could discover verifiable laws and theories that could describe and explain the underlying forces that drove societal change.

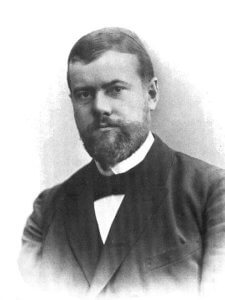

Not all of the academic community, however, agreed with Comte and Durkheim’s scientific approach to the study of society. Indeed, by the mid-nineteenth century, a number of social theorists had started to question whether the scientific method – in its pure and unadulterated form – was an appropriate tool for investigating social matters given the fundamental differences between the natural and social worlds. This growing sense of dissatisfaction led to the development of a new “interpretive” approach to social inquiry – a movement which is often associated with the work of the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920), but which was also heavily influenced by a number of other prominent social theorists of the time, including Harriet Martineau (1802-1876) and Wilhem Dilthey (1833-1911).

The Development of Interpretive Tools of Inquiry

Harriet Martineau was a British journalist, philosopher and social theorist who made her name writing about political and social issues. In 1838 she published a short book, How to Observe Morals and Manners, in which she offered advice to travellers on how to study different cultures and societies, based on her experience of travelling around America. In this pioneering work – which some would argue marked the beginnings of the interpretive movement – Martineau remarked that the investigation of culture and society was quite unlike research conducted within the natural sciences. This was because it involved an altogether different and more diverse subject matter: human beings and their social interactions.

To study human social life, Martineau argued that researchers needed to interact with the subjects of their inquiry so that they could find a way into their “hearts and minds”; an activity that was quite alien to a natural scientist who was trained to impassively observe physical phenomena from afar. Moreover, Martineau believed that social researchers needed to possess “sympathy” for the people or cultural groups they were studying, as this would enable them to gain a deeper understanding of the matters that were most important to them. By “sympathy”, Martineau seems to be referring to a form of emotional intelligence – an ability to connect or empathise with another person’s thoughts and feelings on the basis of a shared sense of humanity. Without the possession of this important skill, she argued, a researcher or traveller would only be able to gain a superficial understanding of another person’s culture and way of life.

Like Martineau, the German philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey believed that the social and natural worlds required different methods of inquiry. He, however, approached this problem from a slightly different angle. He argued that the study of the social world should focus on the human “lived experience”; it was about trying to understand the inner feelings, thoughts and desires of other human beings. Our inability to directly observe other people’s experiences, however, led him to believe that we should study people’s expressions – their outer manifestations – of these experiences. These could range from casual bodily gestures and actions, to more formal examples of speech or writing, or even works of art they had created, such as books, poems, paintings or music.

“To Dilthey, hermeneutic interpretation involved placing oneself in the position of the creator of an expression – the author of a book, the painter of a picture, the giver of a speech – in an attempt to re-experience the original feelings or thoughts which gave rise to their action.”

As part of his work on hermeneutics, Dilthey developed an important concept that is now considered fundamental to the interpretive philosophy: the “hermeneutic circle”. This involves the idea that the interpretation of meaning is always a circular and iterative process: the interpretation of the part always depends on the interpretation of the whole, and the interpretation of the whole depends on the interpretation of the parts. To understand this, it is helpful to think for a moment about the process of reading a book. While the meaning of an entire book is dependent on the meanings of the individual chapters or sentences within it, the meaning of each sentence or chapter is also dependent on the meaning of the book as a whole. If, after reading a book from start to finish, we go back and re-read an individual chapter or sentence then we will develop a new, and deeper understanding of its meaning, because we are re-interpreting the part with reference to our new understanding of the book as a whole……and so this circular, iterative process of interpretation continues, bringing us deeper and deeper levels of understanding.

The work of Dilthey and Martineau was vital to the development of the interpretive tradition. However, it is the German sociologist, Max Weber who is generally credited as the founder of this new movement. Weber drew on the work of Dilthey, Martineau and other social theorists, to develop a new methodology for sociological inquiry that centred upon the study of human social action – his focus was on the ways that people act and interact with one another. Like Martineau and Dilthey, Weber believed that human social life could not be analysed through scientific observation alone; it required an understanding of the subjective meanings that individuals associated with their actions – what they intended, what they hoped to achieve, and/or what emotions they were expressing by acting in a particular way.

“Weber argued that we could access this human world of subjective meaning through verstehen – a German term which can loosely be translated to mean interpretive understanding“

One of Weber’s most famous works The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (which we have written about separately here) was developed using a combination of interpretive and traditional scientific techniques of inquiry. By focusing upon the role of culture and religion in the rise of the capitalist economic order – a topic which had traditionally been tackled from an economic standpoint – Weber was able to make the link between people’s religious attitudes, values and beliefs and the development of modern capitalism in Western Europe. It is now considered one of the most influential sociological works of all time – one which continues to provoke controversy and debate even today.

The Interpretive Tradition Today

While Weber, Martineau and Dilthey laid the foundations for the interpretive approach to social inquiry, the scholars and social theorists that followed them have continued to debate and challenge their ideas, taking the interpretive movement in new and interesting directions. One particularly important debate relates the role of the researcher in the process of inquiry and the impact this has on the type of knowledge they can generate.

A philosopher who has been particularly influential on this issue is Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002). In his book, Truth and Method, Gadamer argued that we can never attain objective knowledge of social reality in a scientific sense. This is because, as humans, we are already embedded in the social world we are researching. We will always, therefore, approach our inquiries with some form of pre-understanding, based upon our background, our history, our culture, our education. And this pre-understanding “prejudices” the way that we view a particular topic, and affects our choices about how to research it.

“Gadamer characterises research as a fusion of horizons: we each have our own perspective – or horizon – that limits the way we see the world; however, through the process of social inquiry, we can connect to other people’s horizons or perspectives“

Gadamer’s theories have had a significant impact on the interpretive tradition, with most interpretive scholars accepting his broad point that our knowledge of the social world can only ever be partial and grounded in a particular perspective. As a relatively modern tradition, however, Gadamer’s arguments – and the arguments of the founders who came before him – continue to be subjected to debate and challenge. This will inevitably lead to new ways of thinking about and doing social research. At present though, the central tenets of the interpretive tradition can broadly be characterised as follows:

- The natural and social worlds are different and so they require different methods of investigation;

- Understanding human social life involves delving into the inner world of subjective meaning; it requires an investigation of the values, beliefs, emotions and attitudes that underlie an individual’s actions and behaviours.

- These subjective meanings cannot be directly observed in a scientific sense, but they can be accessed through “verstehen”– a form of empathic understanding.

- The interpretation of meaning is a circular and iterative process. This is demonstrated by the “hermeneutic circle” whereby the interpretation of the part always depends on the interpretation of the whole, and vice versa.

- As knowledge seekers, we are embedded in the social world we are observing. We will always, therefore, approach our inquiries with some form of pre-understanding. These pre-understandings cannot be removed or temporarily set aside. As such, our knowledge of social matters will always be partial and bound by a particular perspective.

- The goal of interpretive inquiry is not about knowing the world objectively; it is about knowing the world differently.

In future articles we will turn our attention to critical theory, a philosophical approach to inquiry which shares much in common with the interpretive tradition. Critical theorists do not, however, only seek to understand the social world, they also wish to change it for the better.

Further Resources

There are many useful books and articles which expand on the ideas presented in this post. These are mainly written with social researchers and PhD students in mind. However, if you are interested in philosophical ideas about the nature of our knowledge and, in particular the interpretivist approach to inquiry, these texts are well worth a read. They include:

- Michael Crotty’s The Foundations of Social Research.

- Egon Guba’s The Paradigm Dialog which starts with a useful summary of several epistemological positions.

- Robin Usher and David Scott’s Understanding Educational Research which we used to help construct this article. In particular, we recommend the chapter entitled “A Critique of the Neglected Epistemological Assumptions of Educational Research”.

- Todd Goodsell’s essay on The Interpretive Tradition in Social Science which helped inform our approach to this article.

For further video resources on this subject please visit our Mind Attic YouTube channel playlist